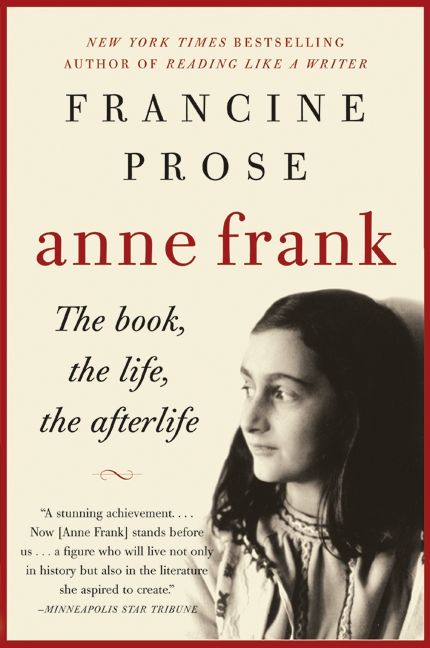

Book: ANNE FRANK, The Book, The Life, The Afterlife by Francine Prose (2009)

Book: ANNE FRANK, The Book, The Life, The Afterlife by Francine Prose (2009) Format: E-book

Owned Since: March 2015

E-books are not my preferred reading format. Batteries die, which is incredibly frustrating, and I hate reading on my phone. But I get at least two daily emails notifying me of cheap e-books, and at least once a week I click the "Buy" button. The Kindle app and the iBooks app are both loaded to both my iPad and my iPhone, and I'm afraid to tally up the number of unread books in my virtual libraries. They're all books I want to read, and I tell myself I'll get to them eventually.

Francine Prose's ANNE FRANK was one of those books. I'm glad I finally got to it. It should go without saying that no one should read this book without reading some edition of Anne Frank's diary first, whether that's THE DIARY OF A YOUNG GIRL, originally published in 1947 (but not in the US until 1952, for reasons Prose explains), or the revised/expanded DEFINITIVE EDITION published in 1995.

I first read the original diary when I was ten or eleven — that would have been fifth or seventh grade — and while it was on a couple of "suggested reading" lists for classes in high school and college, I never took a course that taught it. I've never seen the theatrical adaptation, by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett; and my own mother warned me off the 1959 film version, even though Shelley Winters won an Oscar for her portrayal of Mrs. Van Daan. I've reread THE DIARY several times over the years, and always felt a need to preserve that experience as mine, personally, without any outsiders telling me what to think of it or how to feel about it.

Francine Prose's book was an exception worth making. She gives us Anne Frank the teenager, Anne Frank the writer, Anne Frank the legend and ultimately Anne Frank the industry, walking us from Anne's own determination to be taken seriously as a writer through the wonderful and strange long-term effects her work has had around the world. Prose looks closely at the nature of memoir — as Anne's book ultimately was, since she rewrote the earlier entries herself over the last year of her life — and the difficulty of separating the writer from the work, even after the writer is gone.

Writing is a deeply personal act that creates something separate from the writer, something intended for strangers to read and react to. A writer can't always anticipate a reader's reaction, and certainly can't control it; and yet that writer-reader interaction is so intimate that the better the writer is, the more the reader feels he or she knows the author, and possibly someone the writer knows the reader as well. (See: Stephen King's MISERY.)

We can't know Anne Frank, but Prose shows us how the very action of writing her life down changed her. Measuring things, naming things, changes them; it's a fundamental law of the universe. Anne Frank would have changed more as she found new things to name and measure, and it's still a gaping wound in human history that she didn't get that opportunity.

One problem with reading is that it leads to more reading. A casual reference to Carson McCullers and her husband reminds me that I know almost nothing about Carson McCullers — I had not even known she was married — and makes me think I really ought to read something of hers beyond A Member of the Wedding, which I disliked when I had to read it in seventh grade. I also remember that Flannery O’Connor hated McCullers’ last book, which leads to the thought that I really need to reread The Habit of Being. If I read McCullers, which one should I read?

No comments:

Post a Comment